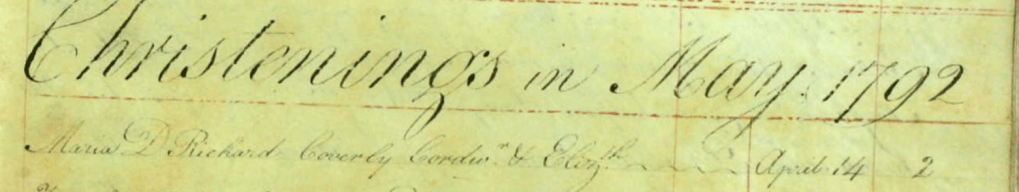

Maria Coverly was born on the 14th April 1792 and baptised on the 2nd May at St Giles Cripplegate, London, England. She was the daughter of Richard Coverly and his wife Elizabeth Burton. This was both of her parents second marriage and her parents had been married the previous August on the 15th, 1791.

At the time they were married both Richard Coverly and his wife Elizabeth Burton were recorded as widower and widow respectively. They were both from the parish of St Luke’s Finsbury. Neither could read nor write as they both signed the banns record with an X as their mark.

It is likely that her father’s first wife Jane Flintoff had died around 1789. It is also possible that they had had some children together. Jane herself had been a widow when she married Richard Coverly on the 1st October 1780 at St Botolph’s in Aldergate. Both of them being from the same parish.

It is also probable that Maria herself may have had some siblings from her parents marriage. Maria’s father and grandfather were both cordwainer’s or shoemakers (makers of leather shoes). These were highly skilled trades and well-respected in their fields. From what I have been able to glean it would appear that the men in the Coverly family had for some generations d been cordwainer’s. The Finsbury area where they came from was a known tradesmen area where cordwainer’s and their families lived and worked. This would have also likely meant a reliable and good income for the little family to live on. Things didn’t work out that way for long though because a few days before Christmas on the 18th December 1796 at the age of forty one and when Maria was only five, her father died.

Countess of Huntingdon’s connexion

Maria’s father and almost certainly her mother had split from the Church of England and joined as ‘dissenters’ the non-conformist religious sect known as the Countess of Huntingdon’s connexion. This was firmly established in 1781 when the Countess ‘dissented’ from the Church of England when she and the local ministers and Bishops could no longer agree on how the faith should be practiced. The Countess was a known philanthropist and had worked tirelessly for forty odd years in the betterment of the unfortunate and in bringing Calvinistic principles to the faithful. She had disagreed with the leaders of the Church of England on what she considered immoderate living and a disregard for the total devotion to Christ that she believed all humans should seek. Leaving the Church of England for commoners alike was no small thing and as such the Coverly’s would have been considered somewhat radical to do so.

What the Countess of Huntingdon did have was the support of the monarchy of the day King George III and his wife Queen Charlotte, who were quite supportive in as much as they could be of her devotion to faith. King George himself had been brought up with strict social mores and devotion to his faith by his mother. As such Maria would have been born into quite a religious and conservative family with moderate living principles and a historical trade in their family line. . How Maria wound up in front of the Old Bailey at the age of twenty bears some imagination.

As her father was a tradesman of London it would be more likely that there would have been some small pension relief fund made available to Maria’s mother through the cordwainer’s trade association. (I’ve been trying to confirm a link with the Worshipful Association of Cordwainer’s since. Even so it is likely that her mother, Elizabeth, would have had to bring in an income of some description for herself and Maria. It is also likely that Maria would have gone into service at a young age possibly as a domestic servant.

Old Bailey London

What happened from age five to twenty is anyone’s guess but sadly Maria didn’t marry a local boy from her church, instead she wound up in front of the Old Bailey charged with theft. At the time she had been employed a very short time by her accuser at a store in Spitalfields Market. Maria was tried at the Old Bailey in Middlesex on the 6th November of 1812. Records from the Old Bailey as follows:

‘MARIA COVALY (name misspelt) was indicted for feloniously stealing, on the 24th of October , three gowns, value 10 s. two petticoats, value 4 s. and one apron, value 1 s. the property of James Smith .

MRS. SMITH. My husband, James Smith , is a leather pipe maker . We live in Castle-Court, Castle-Street, behind Shoreditch Church .

Q. When did you lose these things – A. Come next Saturday it will be a fortnight. I left the prisoner in charge of my place. I went out a little before eleven, and I returned before one; and found the prisoner at the bottom of Wildegate-street.

RICHARD HUTCHINS . I took the prisoner in custody. She confessed to Lock, the officer of the night, that she took the property, and that she would see the procucutrix dead before she should have them.

Q. to Mrs. Smith. How long have you known this woman – A. Only the Tuesday before. I hired her at Spitalfields market.’

So those were fighting words huh! Maria was of course found guilty, recorded as being 21 years of age and sentenced to seven years in Australia for larceny.

Spitalfields Market

Spitalfields Market in Maria’s time was a well established trading and meeting place that serviced the population of the eastern end of London. Establishment for mixed merchandise began when Charles the II in 1682 gave approval for the area (which was already long established) to be a market for the trade of foodstuffs. Much like our shopping malls of today, Spitalfields Market became not only a shopping centre but a place of meeting and trade of all manner of needs and wants.

At the time that Maria was living here, nearby Spitalfields was also an area that was in slow decline. A large Jewish population were moving into the area, many who were escaping pogroms and persecution in eastern Europe and the Russian states. The area was overcrowded. Cheap crowded, slum housing was available for rents that may not have always been able to be paid. There existed a transient workforce with unstable employment due to the struggling British economy at the time. History tells us that the area had a high crime and infant mortality rate ravaged by disease its high transmission not helped by the crowded living.

There are some really fantastic photographs of Spitalfield life that can be found at Spitalfields Ghosts of Old London. These pictures give a bit of a window intothe area that Maria was raised in.

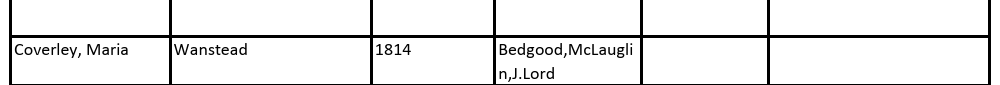

Following what was likely a pretty grim stint in Newgate prison (28th Oct 1812 to August 1813),Maria was eventually transferred onto the convict ship, the Wanstead. The available records from Newgate Prison are unremarkable in that they throw no further light on Maria’s time there other than her admission, purpose of being there and her subsequent ‘delivery’ to the Wanstead. The Wanstead left from Spithead 24th August 1813 under command of its Master and owner, Henry Moore. Unlike many other of the ‘convict’ ships the Wanstead would only once carry a load of unfortunates to the colonies. The Wanstead was considered to have had a successful voyage with only two women convicts of the one hundred and twenty female convicts aboard dying enroute. It would be wrecked off Brazil a few years later in 1816. Three ships left with the Wanstead bound for Australia. These were HMS Akbar, Windham and General Hewett.

Upon arrival in Sydney on the 9th January, 1814, Maria was taken from the Wanstead on the 13th January processed and then transferred up the river as one of a group of sixty eight women to the Parramatta Women’s Factory where she was put to work.

Parramatta Women’s Factory

Maria was transferred to the Women’s Factory along with a fellow shipmate Catherine Latimore, whose grandchild would marry Maria’s grandchild some years later. The two families would eventually make their way to the Hawkesbury. Thus bringing their families together. At this time Maria was 21 years of age.

In 1814 Maria is remarked in the muster of convicts as being a convict ‘on the stores’ (for supplies) and working as a nurse in the hospital.

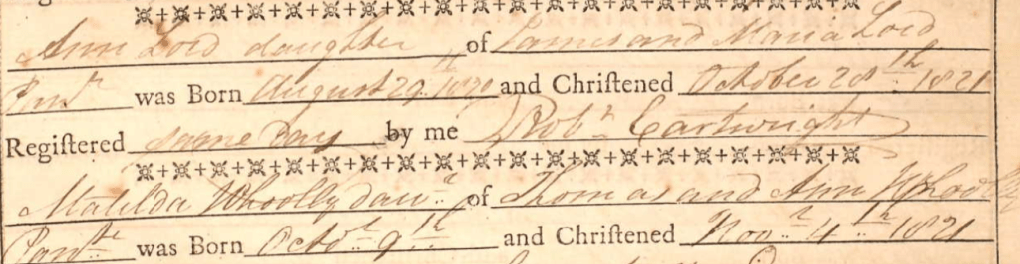

The following year on the 2nd March 1815, Maria gave birth to her first child, Elizabeth Coverley. Maria was not married however a fellow convict William Bidgood, who would call himself William Badgood, was identified as the father and a month later the two of them took baby Elizabeth to St John’s in Parramatta and have her dutifully baptised by the Reverend Samuel Marsden.

William Bidgood was born around 1779/1780, (Sourced from prison hulk records.) I have found references to him recorded as ‘the younger’ so assume his father was William Bidgood the ‘older’ a common reference in those days.

William found trouble in his early twenties and as a result was tried at the Devon Assizes in Exeter on the 16 March 1801 in for sheep stealing. He was convicted and sentenced to transportation for life as a convict to New South Wales. William remained on a prison hulk the Captivity moored in Portsmouth until he came aboard the Glatton September 1802, aged 22, leaving England in September 1802 and arriving on the 11th March 1803.

Bidgood/Badgood Castle Hill Convict Farm

In 1806 William was listed as working for the Government at Castle Hill a convict work farm. Being assigned to a ‘work farm’ was generally an indicator that William was not considered of ‘good enough character’, to be released to work for one of the settlers which was the usual practice for the low-risk convict. He may have got himself in trouble or been considered too troublesome and been sent onto the work-farm to grow food for the colony with other prisoners. I also don’t know whether he had a role or not in the Irish rebellion, Castle Hill Uprising of 4 March 1804. I’ve not been able to find a definitive list of participants in this uprising but do known that while ringleaders were hanged and others ‘put in chains/gibbeted’, some ‘lashed’ with other troublesome convicts sent to the Coal River chain gang. Remaining convicts were threatened with Norfolk Island should all talk of rebellion not immediately desist (considered a fate worse than death), some of the less rebellious convicts were sent back to their employers and to the convict farm. Whether William had any sort of role in this uprising I cannot convincingly establish but I do know he was in the area, he was Irish, he would have known at least some of those involved. (Source, National Library of Australia Castle Hill Rebellion)

On the Castle Hill 1806 transcription records William is recorded as Irish, no religion recorded, surname recorded as Badgood/Bidgood, a government servant serving a life sentence, occupation prisoner. Approximate year of birth not recorded on transcript. Arrived aboard HMS Glatton. (Sources The Hills Shire Council Library, online resources.)

Now I’m not exactly sure yet what happened to William Bidgood/Badgood but he disappears from the scene. The Castle Hill Government Farm operated as a convict farm from 1801 to 1811.

William McCoughland

During 1817 Maria managed to get in front of the Reverend Samuel Marsden again, this time with her new son William who was born on the 13th February. It is hard to work out what is written in the register but I think it is William McGloughland and this is written as his father’s name also. Coverly being how Maria’s surname was spelled in the record. Again Maria is unmarried at the time her son was born. William was baptised in the same church as her daughter at St John’s in Parramatta. What bothers me about this entry is that the person recording it is clearly literate, Maria is not and the spelling is so far off even for those times. A quick search gave me nothing under this spelling. I’m assuming that the spelling is probably Mclaughlan or Mclachlan or mis-spelled for some other reason?

Parramatta Female Factory

by 1819 Maria was living at the Parramatta Female Factory with two children and well into her sentence as a convict. I have not been able to locate any records to the contrary so it would appear that Maria completed her full sentence. It is very unlikely that Maria was living at the Factory through choice and more probable that as she had small children and no husband she was being punished for this socially unforgivable behaviour. Rations described as ‘adequate for rational support’ for a female convict in the factory were two-thirds that of her male counterpart and her children would have received half the ration each of a male. Maria received no payment for the work she performed. Because the children were under three as an unwed mother she could keep them with her at the Factory however, this also probably points with some certainty as to why she wanted to be married by 1820. Otherwise the children would have been removed and put into the Paramatta Orphan School and not necessarily returned to her care.

James Lord

Life for Maria took a definite change on the 7th February 1820 the Colonial Secretaries papers records Maria as Cobley, being given permission to marry another convict, James Lord. James was brought to the colonies on the Lord Eldon. James had been convicted in England of larceny and sentenced to death which was then commuted to transportation. They had sought permission to marry which due to their convict status (even though Maria’s ended in 1819) was a pre-requisite. James was still serving his sentence when they married. As to the constantly differing changes in how Maria’s surname was spelled I doubt she was trying to be coy, rather as woman who could neither read nor write the spelling to her would have been irrelevant and it was probably just how she pronounced it. Note register of marriage is signed with her X along with her new husband’s X.

By 1822 Maria and James Lord were both employed by Mr Williamson, still in the vicinity of Parramatta and living locally. 1823 Maria and James and family were living in Liverpool with both remarked in the census as ‘free’.

The family would move around Sydney somewhat before 1825 when James Lord moved the family up to Richmond in the Hawkesbury. It would appear at this time that both had been employed in work as servants.

John had come from England as a convict arriving on the Lord Eldon in 1817. He had been tried at the Hereford Assizes and sentenced to seven years transportation.

Maria and James would go on to have a number of children, Ann (b 1821), Esther (b 1823), James (b 1823 would die as an infant), Sarah (b 1825 – d 1827 died aged 2), Henrietta (b 1826 died as an infant), male brother unnamed (born and died 1827), John (b 1827), Maria (b 1828 died as an infant), Richard (b 1829).

I cannot begin to imagine for a mother what it must have been to bury five of her ten children. I know things were tough back in those early days of Australia but even so, this seems a profound cruelty to lose so many children under the age of two.

Hawkesbury

On the 24th July 1830 the Sydney Gazette reported that Maria (Lord) had been in front of the Windsor Quarter Sessions charged and found guilty of indecently exposing her person on the 4th of March 1830. She was sentenced to the third class of the Female Factory at the house of corrections for three months. Third-class in the penal system for women meant the lowest class, saved for women of the ‘worst behaviour’ and who could expect to receive the ‘harshest treatment.’ These were the women who were referred to as the criminal class. This would have made Maria thirty-nine years of age at the time. I secured copies of official papers indicating that Maria and another man Thomas More had been accused of being in the vicinity of the riverbank/bed at Windsor where this exposure was said to have happened with an accusation that this was thought to be done to attract illicit attention. There remains some dispute over whether the accusations made were actually factual. Maria’s husband stood bail for her and to the best of my knowledge Maria did not serve time at the factory again.

Now just a bit of context around what it could mean to be in the Parramatta Female Factory. From the records here (quoted verbatim below) are some of the ‘usual’ reasons for being sent to the Factory and punishments meted out to women who were considered to have acted outside societies rules.

“Useless in service”, “runaway from her husband”, “useless being pregnant”, “deranged intellect”, “disobeying”, “given up by her Master”, “common prostitute”, “notorious prostitute”, “absent from her husband”, “illegally at large”, “insolent”, “bad influence on other women”, “infamous”, “escaped”, “stealing peaches from the garden”.

Punishments considered suitable for these women on top of being incarcerated against their will included, “Head shaved and made to wear the cap of shame”, “isolation in cell”, “hard-labour”, “reassigned”, “bread and water”, “son born, sent to Orphan School”.

It would be easy to make judgements from the outside about the supposed character of the convict women of the time, it’s impossible to make any sense of or understand the trauma these women lived.

There is almost no mention of Maria and James in the Hawkesbury in a pioneering sense so I don’t think they were doing particularly well from a financial point of view. James is recorded on the convict register as having died on the 23 November 1833 at the age of forty nine.

In her later years Maria lived with her eldest child, Elizabeth and her son-in-law Edward Mitchell at their property “Fern Hill” at Kurrajong. Maria died on the 1st January 1864 aged seventy-one years. Maria is buried at St Peter’s Anglican Cemetery, Windsor Street in the town of Richmond in ‘the Hawkesbury’.