1839 – The Aberdeen Journal described Tomachlaggan in the parish of Kirkmichael as being only a few miles walk northeast of the village of Tomintoul.

John Riach and Janet Stuart were the last of their line to experience life as traditional highlanders. The world changes that occurred during their lifetime would profoundly alter the direction of their and their descendants lives.

Life in the highlands had for many generations been made up of small villages. Generally no more than a hundred or so to a village. Buildings and holding yards constructed may have lasted for several generations but were made predominantly of natural available materials of the time. Turf, brush and thatch, rough stone, were all used from the surrounds to construct and maintain these buildings as cherished homes. The inside walls could be covered in thick layers of mixed clay and straw to form a weather impenetrable barrier. What people missed out on in limited available standing timber, they were able to make up with limestone and field stone. Limestone being in very good supply around Kirkmichael. Bracken that has since threatened to take over was held in check by the people of the glens. It was used for many diverse purposes one being as mattress stuffing. Possessions were carefully looked after and preserved for each generation.

The throw away and replace society we live in today bearing no resemblance to this earlier world. Travelling into the highlands now and hoping to see standing evidence of these seventeenth and early eighteenth century villages will prove somewhat disheartening. Being made of natural available materials by people who lived in sympathy with their environment meant that once emptied, nature eventually returned the landscape to its rugged origins. A stray stone wall here, an outline of ground level rocks in the shape of a home or a jutting chimney stack may be the occasional and only reminder that this was once a vibrant village of people going about their daily lives. From the middle of the eighteenth century onwards redevelopment and construction was much modernised. Hamlets such as nearby Tomintoul would be completely replaced with a carefully planned and redeveloped replacement.

The failure of the 45 Jacobite Rising would herald the hated clearances of the highlands. These measures emptied the hills and glens. Tight knit familial groups (clans) were systematically dismantled. The highlands had been home to the Scots for nearly a thousand years. The clearance decision was part political, part opportunistic, part reform of agriculture and part forcible expulsion. The clearances removed approximately seventy thousand people permanently from their traditional clan lands. An estimated thirty percent of the inhabitants of the highlands were evicted in a fifty year period. In real terms an area of nearly ten thousand square miles was inhabited by just over eighty thousand people at the end of the clearances. Similar to their Irish neighbours the diaspora of the highlands has resulted today in more descendants of the highlands living outside of Scotland than within it.

John Riach was born in Kirkmichael Banffshire in 1711. On the 4th of August 1733 he married Jannet Stewart (yes the spelling keeps changing) at Kirkmichael in Banffshire.

Where was Janet from? I have my suspicions but I need to prove it. Stewart was too common a name in the area for me to punt a guess. I’ve found her surname spelled a few different ways. Stewart, Stuart, Steuart.

Before long they would welcome a family of children.

21 Sep 1734 James Riach baptised at Kirkmichael, Banff, Scotland son of John Riach and Janet Stuart.

15 Sep 1737 Elspet Riach baptised at Kirkmichael, Banff, Scotland daughter of John Riach and Janet Stuart

8 Mar 1739 Margaret Riach baptised at Kirkmichael, Banff, Scotland, daughter of John Riach and Janet Steuart

27 May 1741 Ann Riach baptised at Kirkmichael, Banff, Scotland, daughter of John Riach and Janet Steuart

When Ann was born the family were living at Tomachlaggan. Which is not to say they weren’t living at Tomachlaggan beforehand, its just this is when I can definitely place them here.

At the age of thirty-four John and Ann were living in a time of uncertainty while raising their family of young children. On the 19th of August, eighty mile south at Glenfinnan, Charles Edward Stuart had landed from the continent, setting off the 1745 Jacobite rebellion. To his supporters he was the Bonnie Prince Charlie. To his opponents he was the Young Pretender or the Young Chevalier.

The reasons for the 1745 uprising are complex. To break it down where it is particularly relevant to us. The Riach family, indeed other local families connected to ours, The Hay’s, The Stuart’s, The Watson’s were all impacted by decisions made in the parliaments of England. These decisions directly threatened their very livelihood. France and England from 1740-1748 were engaged ) in the War of Austrian Succession. The British had blockaded French ships to and from the north eastern coasts of the highlands. The purpose was twofold. One it stymied the French from trade and two it reduced the chance of Jacobites being supplied by the French for another rebellion. Important to keep in mind that the Jacobite rebellion was rebellions of which there were five in total. 1689-1692, 1708, 1715, 1719 and 1745-1746. These rebellions were inter-generational in the minds and lives of the Highlanders.

The French blockade to the north east coast of the highlands effectively cut off highlanders from their primary trading partner. Which was the French. While the return of the Stuarts to the throne of Scotland was political for its adherents, for the everyday highland family it was more about the pragmatic need to trade for survival. This began a period of smuggling and black-markets which further made life more unnecessarily dangerous and challenging for the highlanders. As the financial impact became more grave its understandable that for the ordinary man and woman throwing your lot in with the Stuart’s might mean restoration to a better living for your family and your future. The potential to restore your countries sovereignty through a Scottish King would have been politically desirable but for the common man it wasn’t the primary reason. Additionally to this, the very land you lived on and the sentiments of your landlord would play a crucial part in how you responded to the threats present.

Leading up to the uprising tensions and misinformation contributed to what would eventually lead to hostilities breaking out. The poor English attitude towards the Scottish reflected in their news of the day. Reports from both sides expressed entirely different sentiment.

14 Feb 1744 The Gloucester Journal

London 9 Feb

We hear that the author of faction detected will shortly write a treatise upon public liberality, proving that it ought to have no bounds, and that they who say the contrary are all Jacobites. Some people talk as if the state beagles are busy in smelling after a plot, which it is thought will be a necessary inference from the travels of the young Chevalier. By the great hurry that is now talked of, may it not be suspected that there has lately been too much negligence and security?

Penuel Grant of Ballindaloch wrote to her brother Ludovick Grant in the lead up to Culloden that the people on their lands of Morrinch (in Glenlivet) had been threatened by Glenbucket and his men that if they did not join the highland army they would be plundered. Ludovick Grant wrote that from the 5th of September most of the Strathdown and Glenlivet men had ‘determined to remain at home.’ Further that “numbers of people were flocking into the country with their cattle in order to be happy at home in a few days when Glenbucket is to march from the neighbourhood.” On the 9th of September Glenbucket’s men marched to Gordon Castle where they seized horses and some armaments at Fochabers. By this time Glenbucket had 300 men. Glenbucket wrote to Prince Charles of his frustration that despite his best efforts he could not get more men to join and that often those who did would would not stay and some that had joined early would leave. This of course would have had to be done very surreptitiously being caught as a ‘deserter’ was treated in the harshest of terms. Glenbucke joined forces temporarily with John Hamilton factor to the Duke of Gordon. They would stay around ten days in Banffshire continuing to try to raise men. Grant, C. (1950). GLENBUCKET’S REGIMENT OF FOOT, 1745-46. Journal of the Society for Army Historical Research, 28(113), 31–41. http://www.jstor.org/stable/44220518

Aris’s Birmingham Gazette 18 Nov 1745

Scotland, Copy of a letter from a gentleman at Perth to his friend at Berwick Nov 1.

Notwithstanding the report you have heard of the disaffection of our townsmen, the following instance will fully convince you of the contrary. Last Wednesday being his Majesty’s birth day, 100 Maltmen and some of the Trade Lads, posted themselves at the Church and Steeple and began about midday to ring the bells as is usual on that day, which gave to great offence to Mr Oliphant of the Galk, who is appointed Governor of the town by the Pretender’s son. That he went immediately to order them to desist. Their answer was that they would continue ringing till ten at night and in the evening were bonfires in the streets, and the windows were illuminated, and such as refused to illuminate their houses had their windows broke. About nine o clock our worthy Governor with the advice of the Jacobites (assembled) in the council house in order to defend about 400 stand of arms and ammunition, which were left by the French convoy, sent 15 armed men to disperse the mob, as they called them. Who fired and wounded some of the townmen. Upon this those in the steeple rung the fire bell and their friends beat to arms, the people attacked and soon disarmed their invaders, and belaboured them most heartily. About midnight they began to fire upon the rebels in the council house, who returned the fire. Several of the townspeople were wounded, an Irish French Officer was killed, and many wounded in the council house. Yesterday they sent for and received a reinforcement of 60 of Lord Nairn’s tenants in order to defend themselves, and keep possession of the council house. We are assured there were rejoicing on the King’s birthday in almost every town and village in Scotland, and even in the Neighbourhood of Edinburgh, where the rebels then were.

“The Duke of Cumberland’s troops (English) passed through Banff on the 10th of November 1746 on their way to Culloden. The only exploits by which they signalised their visit were the destruction of the Episcopal chapel and the execution or rather murder of a poor man named Alexander Kinnairkd, from Culvie in the parish of Marnoch. Being found with a stick notched or seen notching it in a way supposed to take account of the boats passing the river with troops, he was taken for a spy, and immediately hanged on a tree, near the site of the present chief hotel.” (The New Statistical Account of Scotland Vol. XIII, last printed 1911)

Excerpts of newspapers reports located specific to Banff follow.

8 Oct 1745 The Western Flying Post

Letters from the north assure that Major General Gordon of Glenbucket has gathered together 2000 horse and foot in the shires of Aberdeen, Banff etc, and that the Mackintoshes, Macphersons, Frasers, Farquarsons etc, are got up and will be in the country this week. We are also assured that the gentlemen of Angus and Mearns are getting on horseback to attend his standard. ( *Major General John Gordon of Glenbucket was a Scottish officer who fought for the Jacobite cause in both the 1715 and 1745 risings. Gordon survived the Battle of Culloden in 1745, escaped to France, where he died in exile in 1750.)

13 Dec 1745 The Caledonian Mercury

Some of the cannons that have passed by Montrose are so large that they require from eighteen to thirty horses to draw each of them and some of the cannonball lying there are 22 lb weight. The main body of the Highlanders are not yet in motion but are counted in several places such as Perth, Dundee, Forfar, Brechin, Montrose, Aberdeen and Banff.

31 Mar 1746 The Western Flying Post

The rebels are said to be moving towards Cullen and Banff, but whether the whole, or only detachments to secure provisions we don’t learn.

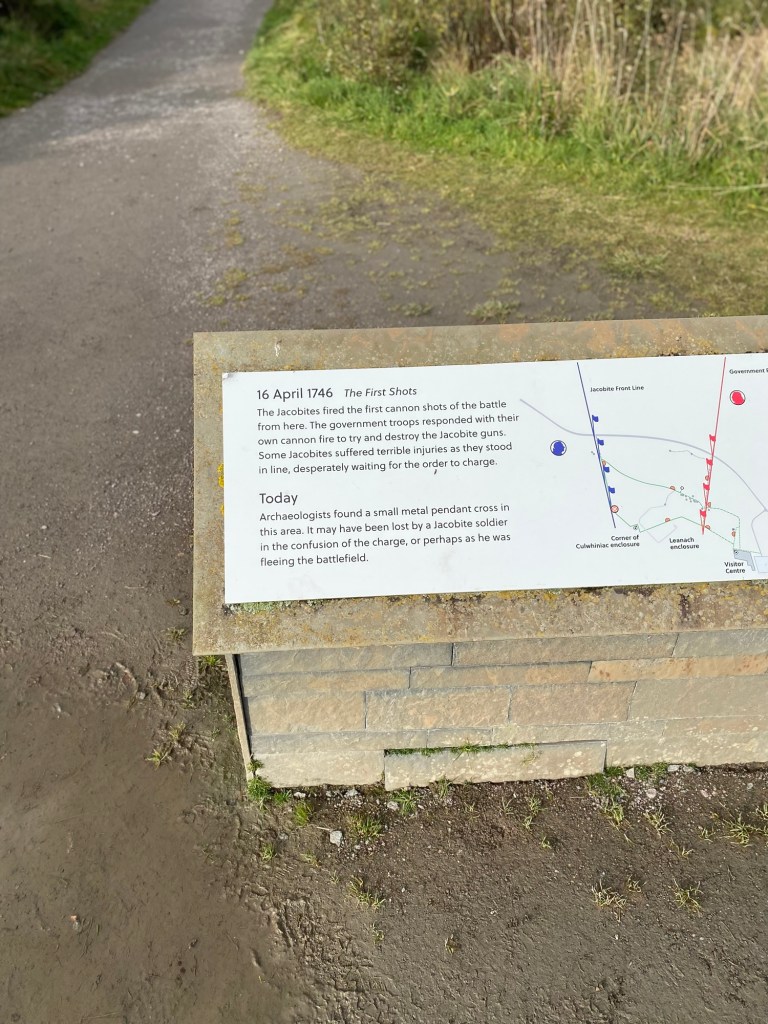

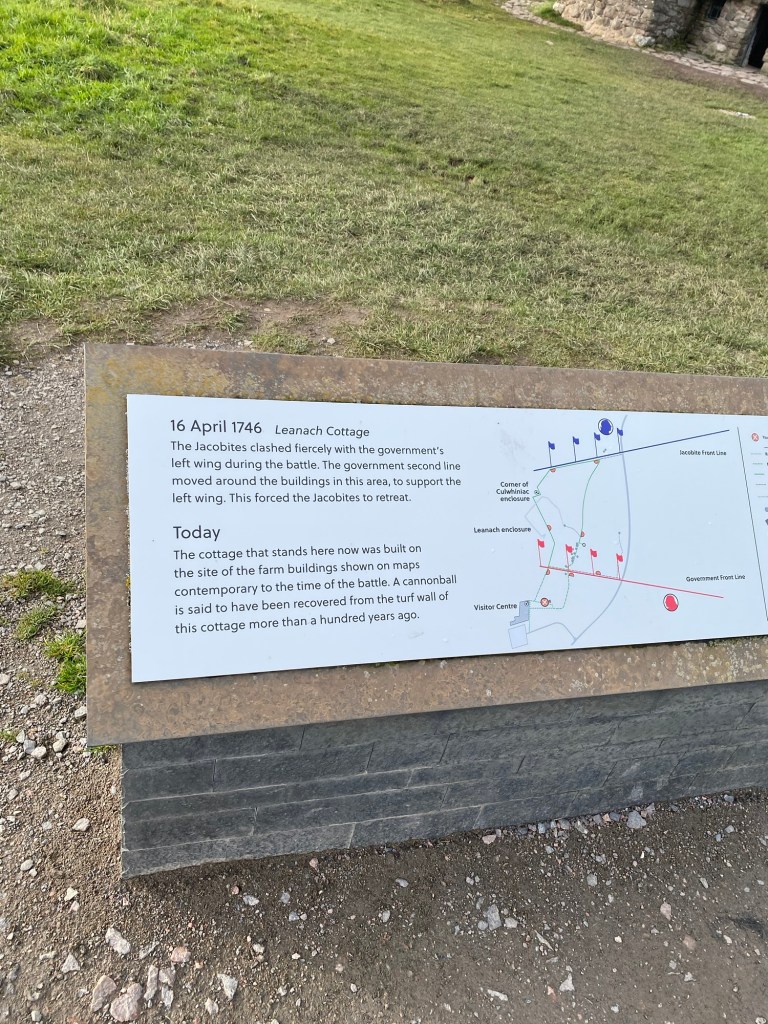

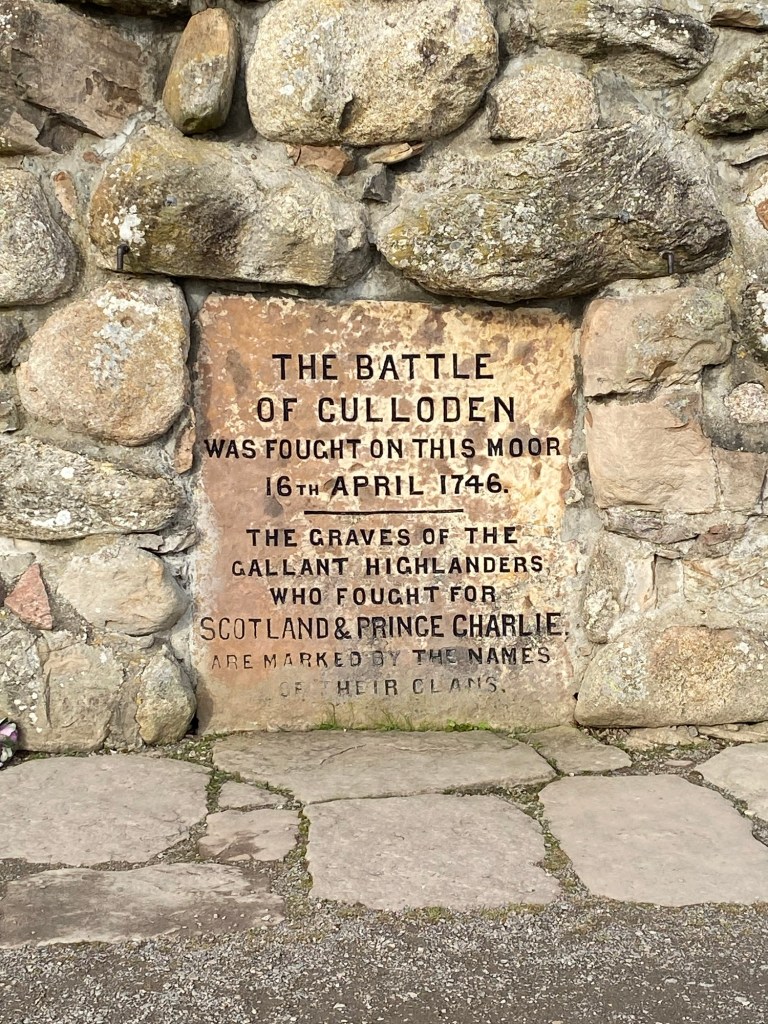

16th of April 1746 The Battle of Culloden, Inverness.

On the 15th of April the highland army drew up in battle array on Culloden Moor Glenbuckets regiment inthe front rank with a strength of 200 men. On the following day it was placed in the second line. when the charge of the right hand regiments of the front took place the Macdonald battalions remained motionless with their right unsupported. The Macdonald were in danger of being surrounded , which made them stop till the Duke of Perth’s and Glenbucket’s regiments were drawn forward from the second line to make up the line. this was at the command of Lord George Murray. “I brought up two regiments from the second line after this, who gave their fire’ but nothing could be done – all was lost”. The last record of Glenbucket’s Regiment. Grant, C. (1950). GLENBUCKET’S REGIMENT OF FOOT, 1745-46. Journal of the Society for Army Historical Research, 28(113), 31–41. http://www.jstor.org/stable/44220518

23 Dec 1746 The Caldedonian Mercury

We have accounts from Banff, that two Companies of the Military stationed at Strathbogie and Keith are very active in apprehending the outstanding Rebels lurking in that Country, and that they are bringing them down to Banff Prison every day.

The failure of the 45 uprising was catastrophic to the inhabitants of the highlands. The long term impacts would be felt for generations. In the period immediately after the battle up to 3,500 people were arrested and incarcerated as Jacobites. Records vary with accuracy as to the outcomes of these. Of these 120, were convicted of being Jacobite leaders and summarily executed as traitors to the Crown. Close to 1300 more would be transported to the colonies as political prisoners. Numbers of those who escaped into exile are uncertain as are the exact numbers who died as a result of wounds, starvation and illness both incarcerated and on the run. The battle of Culloden itself varies with numbers of Jacobite casualties ranging from a thousand to fifteen hundred. This figure includes those who perished on the day and in the days and weeks afterward. The immediate impact has been estimated that around five thousand men (that doesn’t count the women and children), were immediately and irrevocably the recipients of bitter life changing circumstances.

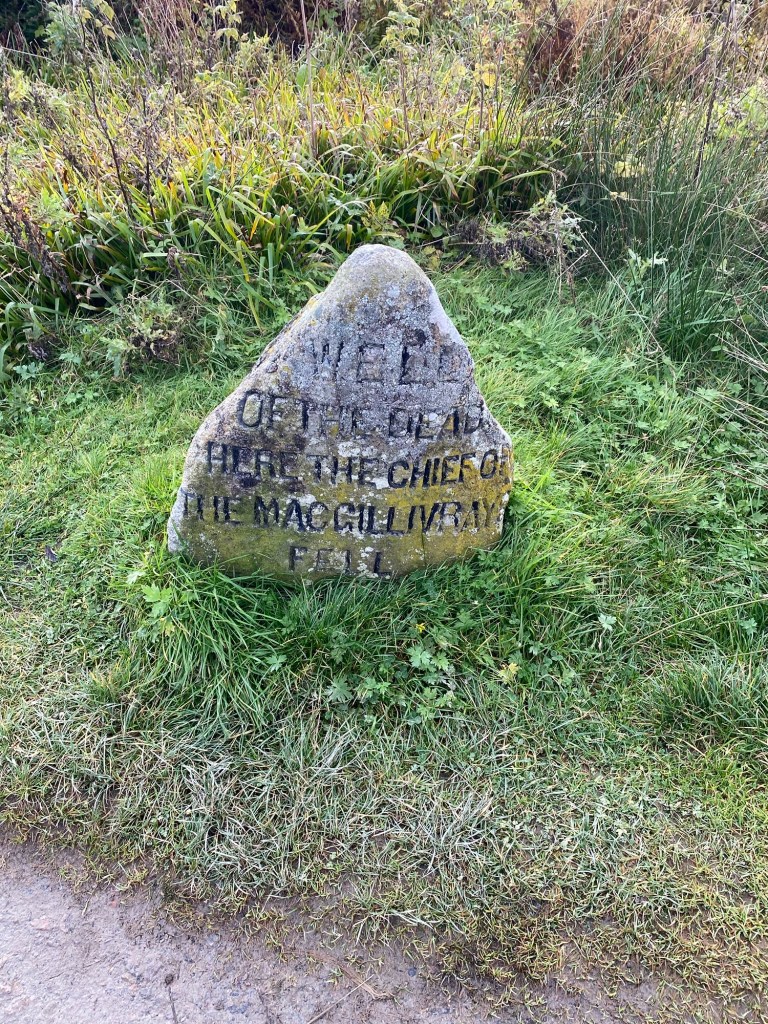

Culloden Moor, Battlefield, 2023.

(all photographs taken by author)

Centrally placed in this were our John Riach and Janet Stuart. From what I’ve been able to secure so far, it appears that they remained in Kirkmichael the whole of their lives. My supposition based on John’s record is that they both died there between 1765 (John aged 54) and potentially 1784- 1794 if Janet lived beyond John(and into her eighties or nineties.) But no more than 1800 would be reasonable. I’m yet to be able to definitively lock these in. 1765 John died in Kirkmichael.

Life in the Parish of Kirkmichael

What was life like for our Riach family living in the Parish of Kirkmichael? There were extensive clearances throughout Banff in the years following Culloden however, our people seem to have escaped the worst of it, and I’ve been able to find some good evidence why I think that is.

In 1794 Rev Mr John Grant of the Parish of Kirkmichael would write and submit to his church superiors a statistical account of the parish of Kirkmichael, in the county of Banff. It was these intermittent statistical reports that would be supplied by all parish heads to the church (Church of Scotland), to give insight into the character, operations, fiscality and moral culture of the parish from which the church could monitor. While these are valuable records often full of information that is rare to find elsewhere, it is important to note that it is written from the view of and for the ecclesiastic community. There should be an expectation for the reader to come across the religious bias reflecting the ecclesiastical morals of the day, incorporating the writers own bias and perhaps frustrations. These were not impartial records. While the writer may make reference to Catholic and other so called non-conformist faiths often referred to as Dissenters, these were written not from the point of reporting on or being concerned for the welfare of these alter faith parishioners just of their existence and possibly their number for comparison. The notes from the Reverend are his recordings but also include those opinions written and expressed in church records of those who filled the role prior to him, whom he refers to as “incumbents”.

1720’s

During this period Alexander Gordon (1678-1728) was the 2nd Duke of Gordon. He was Catholic but married a protestant. With encouragement from his wife the family would transition to Protestantism. He was a Jacobite and fought at the battle of Sherrifsmuir in 1716. He would be imprisoned for a short time before being restored upon the death of his father later the same year. This transition and being seen to align more with the English after the uprising would have had no small percentage of political adroitness to it.

The Reverend records frustration that there are no sessional records in the parish prior to 1725 due to a combination of poor record keeping and inaccuracies caused by in his estimation dissenters and Catholics keeping their own records. This he describes as “the encroaching upon the prerogative of the Established Church.” Moreover that of the Catholics “the priest generally takes the liberty of sharing the functions that belong to the Protestant clergyman.” Further expressions include frustration that when a tax was introduced to register births, marriages and deaths with the church that the parishioners of Kirkmichael had treated this with effrontery and in many cases consequently refused to register. Hence why there was a dearth of consecutive and full records. The reverend refers to them graphically as the “mutilated records of Kirkmichael.” Additionally and please oh please let this be true, the Reverend remarked on the Gaelic epithet of ‘bajaculas’ being expressed by many in response to the expectation that they pay to register family in the church. And if that word still exists, I want to bring it back.

1730s

1728 would see the heritable title pass to Cosmo Gordon, the 3rd Duke of Gordon. He would begin and see through to its unfortunate demise the Lecht Iron Mine.

The Lecht Iron Mine, near Tomintoul, was opened at Kirkmichael in 1730. The mine was operated by the London based York Building Company in a collaborative business venture with the Duke of Gordon using his land. Mined ore was carried out of the hills on horseback to Coulnakyle near Nethbridge to furnaces where it was smelted. The trip from Kirkmichael to Nethbridge being not less than three days each way. For a short period of time there was a plan to bring a railroad to Kirkmichael. However, with the failure of the mine this was abandoned. At its peak of operation, the mine employed sixty men. It would be closed however, a financial failure in 1737 due to the poor quality of minerals mined and rapidly falling market prices for iron.

1740s

“Frosts came in the September of 1740 and the snow fell so deep in October that the corn continued buried under till January and February following.” The cost of meat became exorbitant. “To increase the misery of the people it was often mixed with lime to stretch it. Which proved to many to be fatal.” The Reverend wrote that the ordinary people of the parish took to bloodletting of their animals for sustenance for their families. This was a practice considered archaic and distasteful in all respects. At this time Cosmo Gordon was still the 3rd Duke of Gordon.

1745 – 1746 The final Jacobite Uprising – From the perspective of the record keepers, Cosmo Gordon the son of an avowed Jacobite and Lord of the Gordon clan supported the British Government during the 45 uprising. However, his younger brother Lord Lewis Gordon raised a substantial number of contingents of Jacobites. Reputedly this was often achieved from ‘pressing’ into action tenants from his older brothers vast holdings as well as a great many fellow military men who would rise from his naval connections. Representatives in the uprising from ‘the Gordon’s’ made up a considerable number on the field. Charles Stuart would name Lewis Lord Lieutenant of Aberdeenshire and Banffshire before Culloden. At Culloden Lewis was positioned with the Jacobite reserve and the Franco-Irish troopers of Fitz James Horse. Becoming apparent that the day was lost Lewis would flee for his life to France where he gradually sank into an impenetrable malaise before expiring prematurely in 1754. As a key leader in the Jacobite uprising he had no chance of being pardoned.

The Church of Kirkmichael was built in 1747.

1750s

Alexander Gordon 4th Duke of Gordon 1743-1827 acceded the Dukedom on his father’s death in 1752. He was however not in his majority being only nine years at the time.

The Gordons had long been a committed ‘army’ family. One of the reasons that Alexander Gordon restrained from evicting his tenants during the clearances was that he considered them as natural recruits for the army. Even when tenants could not pay their rents he was likely to overlook this until they could. For this reason.

1760s

1770s

1775 The Duke of Gordon instructs that the thatched and irregular cottages of Tomintoul are to be taken down. The township is rebuilt on his design with much improved material and becomes a thriving centre of commerce for the parish. It’s location also taking advantage of the ancient road through that had been rebuilt. As the village stood on ‘his’ land, he was able to do this and contributed quite significantly from his own finances to achieve this goal.

1780s

The years 1782 and 1783 were reported as being a time of “wretched conditions of the poor here and from the neighbouring counties.” Noted was that the relief of the poor fell to the church to manage. There was expression that this relief was limited from the Church of Scotland only to its adherents with the remark that non-conforming and Catholic members could not expect to be supported by any other than their own communities. The Duke of Gordon was remarked to “have extended a human concern to the distresses of all of his inhabitants by supplying them in meal and feed corn at a moderate price.” None were “known to have died in want” but it was further remarked of the travail of having to provide financial support ongoing for “the poor as is their wont are but a tax upon the affluent.”

1790s

1798 – “The Duke of Gordon leaves them at full liberty each to pursue the occupation most agreeable to them. No monopolies are established here. No restraints upon the industry of the community. All of them fell whisky and all of them drink it. When disengaged from this business, (whisky drinking), the women spin yarn, kiss their inamoratos (male lover), or dance to the discordant sound of an old fiddle. The men when not participating in the amusements of the women, sell small articles of merchandise or let themselves occasionally for days labour, and by these means earn a scanty subsistence for themselves and their families. In moulding human nature, the effects of habit are wonderful to them.” Notes Tomintoul is inhabited by 37 families. Makes reference to the strong desire frequenlty expressed by the local people to return to their thatched ‘hovels’ in the glens and hills rather than live in the redeveloped towns. Continues, “To go into their houses and take a view of their contents, seats covered with dust, children pale and emaciated, parents ill-clothed with care furrowed countenance, His Grace the Duke of Gordon is as much distinguished from many of the other proprietors in the Highlands as by his great and opulent fortune. From that rae which he now prevails for colonising the country with sheep, his Grace is happily exempted”.

The Reverend remarked on the preferred and committed adherence to agriculture as a preferred occupation by his Parishioners. He went so far as to remark that a tailor or shoemaker wouldn’t have much occupation here but a law-person might by dint of the amount of requested litigation. Of the numbers of beasts in the parish the following was recorded. 1400 black cattle, 7050 sheep, 310 goats, 303 horses. No other domesticated animals reared in farming other than poultry and a few geese.

It is recorded that the Church of Kirkmichael was built in 1747 but since then has been allowed through the neglect of the local people (dearth of financial contributions) to fall into disrepair. That bad roads made many of the areas impassable especially in times of bad weather. That gullies could become awash at these times with glens not able to be passed through. The reverend remarked that rather than the parishioners contribute financially to the repair of the broken glass window panes in the church that they remarked they enjoyed the breeze offered them in warmer months through the window holes but complained of the cold in the deep of winter. By 1786, The writer bemoans the scarcity of his stipend to live and operate the parish from. That from 1717 – 1786 this had remained uncommonly small for all incumbents in his role. He does however write that when he made the Duke of Gordon aware of his pecuniary circumstances that the Duke increased his stipend to a more comfortable amount, without complaint or objection.

The Dukes of Gordon’s stories are intertwined with our Riach, Stuart, Hay and Watson families of the Parish of Kirkmichael. And while it is very tempting to try and link yourself in especially on sites like Ancestry where those little pale green pop ups pique your interest. The reality is, the chance of us being descendants of this family is zip. We were tenants and it would take a mountain of critical evidence to convince me otherwise.

So why am I including them here in this story. Well for very good reason. The story of the Jacobites as previously mentioned is complex. Even within the Gordon family and connections it was not uncommon for siblings to be on opposing sides of the conflict. Nothing happened in a vacuum. Because our family lived and leased the land that was owned by this family, our fortunes were inextricably tied to theirs. To this end please use the below button to link to Jonathon Spangler’s excellent resource which might give you some insight as to why it is possible and indeed likely that some of our Riach, Watson, Hay, Stuart ancestors may have well served during the risings in the cause of the Gordons. More to the point they possibly served on both sides of the conflict.

Lewis Gordon 3rd Marquess of Huntly. 1626-1653. Fought on both sides in the English Civil War. With the Royalist army and then with the Scottish Covenantors. (Catholic) –

George Gordon the 1st Duke of Gordon 1643-1716. Married Lady Elizabeth Howard, daughter of Henry Howard, Duke of Norfolk. Close links with the French. (Catholic). Became the 1st Duke of Gordon because his family were Catholic by James VII when he ascended the throne.

Alexander Gordon the 2nd Duke of Gordon 1678-1728. Married Lady Henrietta Mordaunt, , daughter of Charles Mordaunt, 3rd Earl of Peterborough (Catholic) He would be often known by his military title General Alexander Gordon. He fought with the Jacobites at the battle of Shriffmuir 1716. He would be imprisoned for his participation but restored to his inheritence when his father died the same year. Alexander Gordon was a Jacobite. Through his wifes influence would transition the family to Protestant.

Cosmo Gordon the 3rd Duke of Gordon 1720-1752. Died aged 32. Married Lady Catherine Gordon, daughter of William the Earl of Aberdeen. Died while in France, cause of death, indeterminate. Brought back to Scotland to interred. Protestant.

Alexander Gordon 4th Duke of Gordon 1743-1827. (this is our man who rebuilt Tomintoul.) First wife was Jane the daughter of Sir William Maxwell 3rd Baronet of Monreith. This was recorded as particularly difficult and estranged marriage. After her death he married Jane Christie 1820, a commoner with whom he already had four children. He outlived Jane and died in 1827. (Protestant)

This Gordon line became extinct in 1836 with the death of the 5th Duke of Gordon with no legitimate issue. The estates would pass to the 5th Dukes sister Charlotte, the Duchess of Richmond. Her son, the next heir of the estates styled himself as Gordon-Lennox. Our line via Robert Hay had left the parish of Kirkmichael before this time.

Now, a bit more about- the Hay Jacobite’s of Banffshire.

Janet Stuart and John Riach’s daughter Ann would marry James Hay. Ann Riach and James Hay were the parents of Robert Hay. Our Robert was our convict and first of his line in our family story of Hay’s in Australia.

I would love to claim Andrew Hay (1713-1789) (the Younger) of Rannas as one of our ancestors. Maybe he was a relation. And maybe our Hay’s were just good local farmer tenants in the general area who had nothing to do with him at all. As romantic as it sounds, I think I’m reaching. I’m pretty sure our Hay’s were just ordinary people and had been for a very long time. Rannas or Rannes (historical spelling varies), had been the home of this branch of the Hay Clan nobility under Sasine (or Scottish law) for generations. Why is he relevant to us you ask? Good question. Well, Rannas, was/is located in Banffshire. Which just happens to be where our Hays are from.

There is so much I like about Andrew Hay. He was a Jacobite in the ‘45’ rising. He joined ‘Bonnie Prince Charlie’, the king who never was. He participated in the battles of Prestonpans, Falkirk, Derby and at the fateful Culloden (1746). He was remarked to be a tower of a man standing over seven foot tall. He would have been fear inducing as he entered the battlefield. Andrew Hay led men from Clan Hay onto Culloden and unlike many, he had the very rare fortune to be able to leave the battlefield, almost by the skin of his teeth. He managed to evade the pursuing King’s forces and make his way back to Banffshire. Largely because knowing the area he chose not the direct exit route of many who would be captured but a roundabout entry to his county. Andrew’s father (Charles the Older Rannas) had wisely not directly engaged in the conflict and was able to retain his lands and consequent income from them. He had been a Jacobite in the 1715 which had caused him enough problems.

The next five years in Banffshire was a mix of being hidden. Which at over seven feet was no small feat. Sometimes in homes, sometimes in the woods, hills and even caves and sometimes, very rarely at his home, where his mother hid him. A well organised network clan kept him hidden. He was never caught. Considering the many raids by British soldiers into Banffshire during these years seeking to round up him and other Jacobite’s it’s a surprise that he managed to be so evasive. In 1751 Andrew’s father died. It was now too dangerous for Andrew to remain in Scotland. By 1752 Andrew had been convinced by his mother (Helen Fraser) that he must leave Scotland for exile. He headed for France and the continent. Helen would continue to financially support Andrew throughout his exile.

Use the button here to access Leith-Hay.org which includes a fabulous E book link to Andrew Hay of Rannas – A Jacobite Exile by Alistair and Henrietta Tayler (1937). Alexander Maclehose & Co, London.

After many years of exile and much lobbying by 1780 Andrew was able to receive a pardon and return to Scotland. The timely change of monarch to George III likely a contributing factor to this. Andrew returned to Banffshire and to the Rannas estate to which he was the heir. The ancient family home at Rannas had been burned to the ground in 1759. An estate home replaced the previous Rannas Hall. Andrew would reside there the remainder of his life alongside his sister Jean until his death a few years later in 1789. As there was no direct successional heir upon his death, the title (Rannas) died out, with Jean’s son inheriting and combining his father’s name of Leith with his uncle’s Hay forming the Leith Hay branch of the family.